But that wasn't enough for its parent company, Altria, headquartered in

Virginia. Despite owning the dominant wine company in the Pacific

Northwest, Altria is a giant tobacco company (yes, tobacco!),

whose brands include Philip Morris and Marlboro. Over the past several

years it has been making huge investments in new tobacco alternatives

like Juul; SMWE, the odd duck in its portfolio, could provide a revenue

windfall. When a private equity firm in Manhattan offered to buy its

wine business for $1.2 billion, Altria said yes.

But how did Altria come to own SMWE in the first place? In 2008, Altria

bought a modest, family-owned, smokeless-tobacco company (Skoal,

Copenhagen) called UST, and UST happened to own SMWE. And how did that deal come about? Half a century down the line, it still

seems improbable. Here, virtually ignored by Ste. Michelle's official

history, is the almost unknown story.

On February 23, 1973, two Seattle men disembarked from an overnight

flight on a TWA DC-8 Stratocaster and took a limo from La Guardia

airport on Long Island to Greenwich, Connecticut, some 30 miles

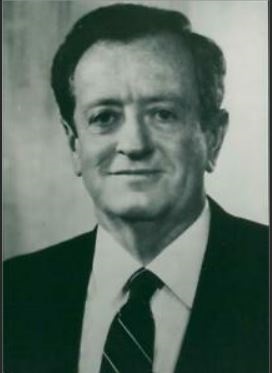

northeast along the north shore of Long Island Sound. The chairman of a

family-owned company that called itself United States Tobacco, a

courtly, 52-year-old gent named Louis F. Bantle, who had inherited the

company from his father, was expecting them.

The Seattle visitors might have been cast as Mutt and Jeff in a black

& white comedy. Joel Klein was six feet, six inches tall,

soft-spoken, and serious. Wally Opdycke had a shock of curly black hair

but stood almost a foot shorter, ebullient, with mischievous eyes.

Bantle offered his visitors a Kool from his silver cigarette case, but

they declined. Bantle's company marketed Copenhagen and Skoal smokeless

tobacco and had an 80 percent market share. Bantle's innovation at US

Tobacco was the creation of flavored Skoal sticks, which at one point

were used regularly by 40 percent of American males under the age of

25. "Before you go, you boys have got to see the museum," Bantle said.

That would be the two-story brick colonial house in front of the sleek

office building that housed UST. On display inside were cigar-store

Indians, spittoons, hookas, and a three-foot Meerschaum pipe. "I'll bet

that drives Dr. Koop nuts," Klein said, referring to the U.S.

Surgeon-General, a lifelong crusader against tobacco.

The Seattle visitors might have been cast as Mutt and Jeff in a black

& white comedy. Joel Klein was six feet, six inches tall,

soft-spoken, and serious. Wally Opdycke had a shock of curly black hair

but stood almost a foot shorter, ebullient, with mischievous eyes.

Bantle offered his visitors a Kool from his silver cigarette case, but

they declined. Bantle's company marketed Copenhagen and Skoal smokeless

tobacco and had an 80 percent market share. Bantle's innovation at US

Tobacco was the creation of flavored Skoal sticks, which at one point

were used regularly by 40 percent of American males under the age of

25. "Before you go, you boys have got to see the museum," Bantle said.

That would be the two-story brick colonial house in front of the sleek

office building that housed UST. On display inside were cigar-store

Indians, spittoons, hookas, and a three-foot Meerschaum pipe. "I'll bet

that drives Dr. Koop nuts," Klein said, referring to the U.S.

Surgeon-General, a lifelong crusader against tobacco.

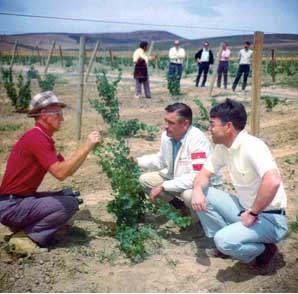

Walter clore (left), Wally Opdycke (right)

Opdycke and Klein had not come to talk to Bantle about tobacco,

however, but about wine. Until the previous year, Opdycke had been a

math whiz who worked as a business analyst for Safeco Insurance, which

was headquartered in Seattle. Looking for safe investments, Opdycke

came upon a rundown company in a south Seattle warehouse called NAWICO,

the North American Wine Company, which had not succumbed to Prohibition

and still held a federal license to produce alcohol. Opdycke wrote a

business plan for Safeco to buy the winery, which had been making fruit

wine, and get into the fine wine business like Mondavi in California.

There was, Opdycke had heard, a PhD professor named Walter Clore who

was going around eastern Washington urging hop farmers and cherry

orchardists to uproot their orchards and plant grape vines instead.

Safeco executives were not impressed, however, and turned Opdycke down.

But Opdycke was convinced of his plan's merits. He sent in his

resignation, rounded up a few friends (among them, super-lawyer Mike

Garvey), and bought NAWICO for himself. He knew he'd need a

professional wine maker, and asked the dean of the only American

university that trained people in the science of fermentation: the

University of California at Davis, whose program was known as Budweiser

U. That's where Opdycke found Klein, who moved to Seattle in 1975.

The realities of the marketplace soon made it clear that Opdycke would

not be able to carry out his plans to start a winery on his own. For

one thing, there were very few locally grown wine grapes available. For

another, the facilities in south Seattle left much to be desired. But

Opdycke had a plan. The federal agency which regulated alcohol also

regulated tobacco, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms. So

Opdycke had read up on tobacco companies, which, it turned out, made

huge profits. They could afford to spend millions of dollars on

marketing, advertising, promotions, and sponsorships because the

margins on their products were astronomical. Insurance companies were

satisfied with two and three percent return on their investments

because they needed to be safe and predictable. The cost of production

for tobacco companies was minuscule by comparison; a two-dollar pouch

of Copenhagen cost Bantle seven cents to manufacture. In 1971, the year

before Opdycke came calling, US Tobacco had net profits of $250 million

on sales of $650 million.

The surprise, today, is that this wasn't more widely known, but US

Tobacco, one needs to remember, was privately held and didn't need to

disclose its operating statements. Tobacco stocks that were listed on

the New York exchange were high fliers: Philip Morris, JP Lorillard,

British-American Tobacco.

Klein did a show-and-tell for Bantle, using objects from his desk, to

demonstrate the tilt of the earth, its rotation relative to the sun,

and the result: during the growing season, the higher latitudes of the

Yakima Valley get more daylight hours than Bordeaux or Burgundy, or

even California's Napa Valley, and it is sunlight, not heat, that

matures the grapes. Yes, winters get really cold, and the vine goes

truly dormant, but then it comes back the following spring with

astonishing vigor.

Klein did a show-and-tell for Bantle, using objects from his desk, to

demonstrate the tilt of the earth, its rotation relative to the sun,

and the result: during the growing season, the higher latitudes of the

Yakima Valley get more daylight hours than Bordeaux or Burgundy, or

even California's Napa Valley, and it is sunlight, not heat, that

matures the grapes. Yes, winters get really cold, and the vine goes

truly dormant, but then it comes back the following spring with

astonishing vigor.

Louis F. Bantle

Opdycke talked numbers: fifty million dollars or so to buy land and

plant vineyards, another fifty million or so to build new facilities (a

showplace headquarters close to Seattle, production facilities adjacent

to the vineyards). They would soon realize you can't push wine through

a pipeline, they would need to build a nationwide sales and

distribution network to create demand and suck out the juice. (Another

fifty million or so.) Bantle began nodding appreciatively. But he

didn't want to write a check for $100 million; he wanted to buy the

company. For half a year's worth of the company's annual profits, UST

would dominate a new industry. By the time Opdycke and Klein got back

in the limo, they had a deal.

"You effing did it!" one imagines Klein high-fiving Opdycke in the

parking lot. "You got this tobacco dude to underwrite the entire

Northwest wine industry!" (Four decades later, then-CEO Ted Baseler

reiterated this: "Ste. Michelle created the Washington wine industry

with UST cash," he told me.)

When the Port of Seattle needed to expand soon thereafter and exercised

its right of eminent domain to take over the old Pomerelle facility in

South Seattle, Opdycke was not worried. He had his eye on an 85-acre

property called Hollywood Farm, outside a bedroom community,

Woodinville, east of Lake Washington. It had belonged to Frederick

Stimson, the timber baron, and was now for sale. Here Opdycke would

build a European-style showplace for his winery, Chateau Ste. Michelle.

(Why "Ste. Michelle"? It was Opdycke's daughter, the story goes, who

said it was high time to name a winery "for a girl.")